Click here to Open the PDF to Print or Download The Tips and Tricks Sheet “The Road Les Traveled.”

The Road Les Traveled

Les Rose, Father, Friend and Photojournalist, a Professional News Organization, Los Angeles Bureau

“You mean they are paying me for this?”

Think about this: we meet terrific people, travel the world (OK, at least our county), and experience more in a year than most folks do in several lifetimes. We never know who we are going to meet, where we are going to go, or what we are going to learn.

But journalism is much more than that. Reporters, producers, writers, anchors, editors, and photojournalists actually have a chance to contribute to society and help people on a daily basis. Imagine! Careers where you get to enlighten, encourage, and inform.

Here are a few things that I have learned along the way, usually the hard way.

1. Passion, People and Pursuits

Every great story is about people. The people we cover include our central characters in the story, the supporting characters, and sometimes officials. The viewers are making the investment of their time. These are some of the “stakeholders” of the story.

We as journalists work for the viewer. We represent them and they trust us to be there for them, literally. We earn their trust in being thorough, thoughtful, and reducing harm whenever possible. Just because the mayor is the suspect does not mean his teenage daughter is also a suspect.

REMEMBER THIS: EVERY GREAT STORY IS ABOUT PEOPLE.

2. What we do

Imagine that you are not working for your company but for yourself. If you have had a story on the air that just didn’t cut it, who do you blame? The whole essence of becoming better is to simply do your best work every single day. Push yourself on the mundane stories. The great stories will come, but if you practice and stretch yourself on the dull daily stories you will be ready for the big ones.

REMEMBER THIS: PRACTICE YOUR SKILLS ON THE DULL DAYS.

3. Silence (really) is Golden

a. Natural sound is critical. Write to it precisely, not generically. Silence is the hardest thing to write to, and can be the most powerful moment in the story. It gives the viewer a moment to focus on what it is like to BE that person.

b. Imagine that your story is about the sole survivor of a school bus crash and you are allowed to shoot some of his rehab. Simply let a scene play out. His struggle just to take a step. His sigh of frustration. These elements will say more than anything you could write. Make the rest of your tracks shorter to allow for this powerful moment. Silence is not a waste of time. The very best use it and it speaks volumes in their reporting.

KEEP IN MIND: QUIET MOMENTS MAKE A GREAT STORY.

4. Leave the gear in the car for better interviews

a. Leave the gear in the car and have the photojournalist and reporter team walk around the home of your subject for just a few minutes. You will get a much better interview and story. Here’s how:

b. First of all, think of what it is like to be on the other side of the camera. We journalists take it for granted. To most people interviews are genuinely intimidating. Though the person is about to be interviewed, you will never say the word “interview” in front of them. Instead, you are going to have is a chat, a conversation.

c. Nobody wants to talk to a stranger, especially with a camera rolling. Here’s a terrific tip to put your subject at ease. Talk about…yourself. Photojournalists, reporters; whoever is there from the newsroom, need to talk to their interviewees.

Like most things worth doing, it may take a little practice. Reporters can be notorious for not wanting the photojournalist to discuss the subject at hand for fear the interviewee will say the best sound bite when the camera’s not rolling. The chat can be about anything you might have in common: but know this; small talk can lead to one great interview, and a great story.

d. During these few moments of conversation, the photographer is also looking for a decent place to do the interview and a different place get the set-up pictures that help tell the story. Then they excuse themselves, saying they’re going outside to “get my stuff” or “get the gear.” Either is less intimidating than “I’ll be back with the CAMERA.”

e. Here’s the best part: when the photojournalist walks back into the house, the subject now regards them as a person with a camera, NOT a camera person. A huge difference! They know the photographer a little more, the reporter a bit more, and are definitely more relaxed. No, you can’t do this on breaking news!

KEEP IN MIND: QUICKLY PUT YOUR SUBJECTS AT EASE.

5. The “Golden Rule” Rules

a. Never forget that when doing a story, give a moment to think about how YOU would want to be portrayed. Would you want your moment on television, your story, to be “sprayed”? I didn’t think so. Your subject trusts you to be fair, accurate, and professional. Hopefully, your work ethic will not let you be mediocre on any story. Remember: Some stories count more than others, but every story counts. Be a human being. Be the best you can be, and sleep soundly.

6. Ten Minutes is Always Ten Minutes

a. Those ten minutes on the way to the story are just as long as those ten minutes before the story airs. Journalists are the only people I know that watch the clock hoping the workday is longer. Time is your greatest asset and your most ominous foe. Use it wisely. Instead of discussing last night’s movie or where you’re going for lunch, make a “commitment” to the story, on the way to it.

b. The commitment is the initial story “kernel” and structure. More importantly, it’s the process of trying to figure out the story’s central character, supporting characters and a possible stand-up bridge. When you step out of your car all of that preparation can change (and SHOULD change). At least you’ve developed and begun focusing on the raw story structure and can have a “feel” for the story before getting there. This lets you hit the ground running with a story “roadmap” in your brain.

c. Remember, you are thinking ahead: What will be needed? Where should you do the key interview? Who should it be? What are the controversies? What sides should you cover? Yes, there are usually more than two sides to a story. What else have I missed?

d. On the drive back to the station, you are trying to layout and edit the story before you enter an editing room. You and your photojournalist are writing the story together: discussing the great moments, pictures, and sound that will make your story the one folks remember.

KEEP IN MIND: PRODUCE THE STORY EN ROUTE.

7. “Walk around and sit a spell”

a. People ask me “How do you find a great character in a story?” Sometimes, they find you. Pre-interviewing is what most journalists do. It often works fine, but NEVER promise somebody they’re going to be on TV. Just walk around and listen. Close your eyes for a second. Really LISTEN, and you just might HEAR the great character before you see them. Sometimes, the loudest voice at a scene can be the greatest character. Sometimes, the softest voice can be the greatest character too. They may bring focus and clarity in a breaking news sea of confusion.

8. “Doughnut Diplomacy”

a. If ever there was a collaborative effort, it’s a newsroom. If the newscast were a rock band and the anchors are the lead singers and the reporters are the lead guitarists, and then the photojournalists are the rhythm section. At least they get some glory. Newsroom colleagues make your professional life possible. Often, they get the least recognition.

b. Be the one in the newsroom to remember these colleagues. If you’re lucky enough to win a regional Emmy, buy some of those “for contributing to an Emmy” certificates for the assignment desk, the tape librarian, the graphic artists, and the ENG maintenance folks who helped you get that award. They also help you daily.

These co-workers get a fraction of the credit you receive, but they deserve their time in the sun too. More importantly, when there is praise from the boss for a story, share the praise immediately with everyone else who was instrumental in making it happen.

Every photographer I know has stood next to some reporter in a local newsroom as their boss congratulates him or her on their great “Storm” report in last night’s newscast. Good for him or her. But, the reporter acts like the photographer that also helped make it happen is a piece of furniture. Like they said in the movie; “Always do the right thing.”

Want to work with the same reporter or photojournalist on a daily basis? Terrific idea! Trust, quality, and great stories go together. Try Monday morning quarterbacking (looking at last week’s stories) to tweak what will work better next time.

Don’t do it the same night your story airs. You don’t have enough perspective. Eventually, you’ll both develop a similar vision.

Let the assignment desk know you want this team to happen. Is the desk just not hearing your request? Those tyrants! Figure out if they like their cake donuts chocolate covered or jelly filled. Recognize the unrecognized.

KEEP IN MIND: REMEMBER YOUR COLLEAGUES.

9. Contests are not for a mediocre meal

a. You need to enter contests. You don’t do it for your ego, your rented tux or the chicken dinners with questionable gravy. You do it so you and your working partner can gather the best four or five stories of the year and figure out what worked and why.

By searching through the archives and figuring out what DID work, you will see lots of stories that did NOT work. You will learn a lot from your failures and near misses. . Don’t get me wrong: it is great to win. It’s more rewarding to get better at your craft.

10. “You can’t hug your job”

a. My friend John Gross, a renowned NFL films photographer, told me this when my wife was pregnant with my first son. “Your family and friends deserve equal time and even better treatment. You will be a better storyteller and a better person if you have varied interests and relationships.” It’s really true.

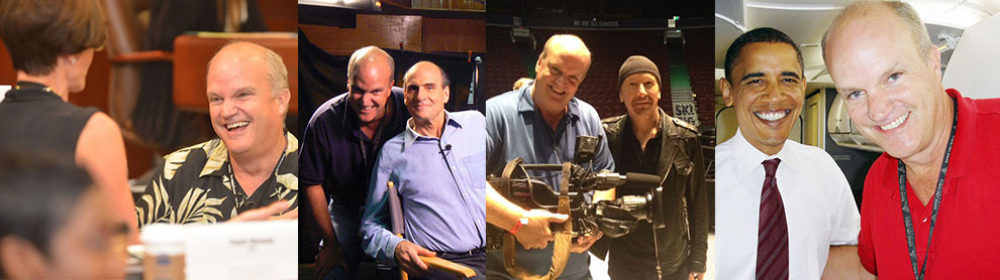

b. My coverage of children’s issues improved significantly because I have two sons that I love more each passing day. It gives me added emotional investment in my work, and it shows. It’s also natural that a sports fan will cover sports better than somebody who’s n ot a sports fan. My passion is rock and roll (over 800 shows so far and counting). Thanks to that passion, I have shot numerous Sunday Morning shoots that involve music. So far that has included Eric Clapton, James Taylor, Carole King, Neil Diamond, David Crosby, Quincy Jones, Bonnie Raitt, and k d lang, to name a few. I never get the Super Bowl and that is OK. I’ll take Clapton.

c. Volunteering, learning a craft, and even joining a gym will expand your circle of friends and broaden your horizons. You will also be much better off having a life outside of work should you ever lose your job. That reminds me, keep your resume and tape absolutely up to date. You never know when your time at your station is up, or opportunity emails.

d. Many reporters take community one step further and get story ideas by being active in a neighborhood other than their own. They get involved at places like a Boys Club, Big Brothers or Big Sisters, or their kids’ school.

KEEP IN MIND: HAVE A LIFE OUTSIDE OF WORK!

11. Surround yourself with greatness

a. For TV photojournalists, watch a classic movie (like Citizen Kane) with the sound off. You will learn a lot about composition, lighting, editing, and storytelling. For everyone, study the story structure of 60 Minutes, CBS Sunday Morning, and top network news reporters you respect. Watch the stories 10, 20, 30 times until they are part of your DNA. Know that great news stories are really short movies in themselves. They have a great beginning, middle, and an end. They have the most information in the middle. They have a way of pulling you in and keeping you. Along the way they offer little surprises or “Gold Coins” as they say at the Poynter Institute. The great stories have motivating moments and memorable characters, but not too many characters. They take you on a journey and they inform you. They may make you feel something. Al Tompkins, Broadcast/Online Group Leader at Poynter, and a great friend, says, “We always remember what we feel long after what we learn.”

b. Sometimes a great TV commercial can tell a story, make you feel something, and sell you a product in just 30 seconds. Try to do that just once. If you need inspiration for your writing, read the greats for inspiration. Shakespeare, Hunter S. Thompson, or Dr. Seuss; whoever you admire. For photographers, find a quiet spot in the library and curl up with an Ansel Adams coffee table book or a book of the Pulitzer Prize winners. The web will give you the great minds and pictures in the comfort of your casa.

KEEP IN MIND: STUDY THE GREATS OF YOUR CRAFT.

12. For photojournalists: Get the moment. Make sure your reporter knows about them!

a. Real human moments are the stock in trade of great television journalists. I am convinced that 90 percent of photojournalism is being a psychiatrist. Photojournalists must anticipate what a human being is going to do BEFORE they do it. You have to be white balanced, focused, rock steady, microphone ready, and rolling (of course) to get the moment. A great moment in a story is simply everything.

A handicapped child walking without crutches for the first time.

A two year old comforting his Mother with a sweet pat on the back during his father’s military funeral.

The one-toothed grandma in the stands cheering on her victorious team.

This is the stuff of life. Capture a great moment in your piece and your audience will return the next day. At least that’s the goal. But don’t forget to work closely with your reporter. Let them know about the “catch of the day.”

b. We all get way too involved in the other 10 percent of photojournalism: things like technical stuff, operating a piece of equipment, and superficial things that don’t propel the story.

Frankly, I don’t know the model number of my camera; I just want it to work. The camera is simply a tool to tell a story. If you get a great human moment, not a soul will notice the lack of backlighting or that you hand held the camera. They will know that they felt something. Something that was real. You made your audience part of the story. You took them beyond just watching.

c. Reporters must remember this too. They must write to the “edges of the video,” as the terrific Bob Dotson of NBC’s Today Show would say. It’s not “see Spot run after the Frisbee” as he is chasing the Frisbee in the park. We can see that; it’s obvious. Try “Spot is having one terrific day” instead.

KEEP IN MIND: GET A REAL MOMENT.

13. Feature Stories- harder to do than hard news.

a. OK, not all of the time. But the point is most of what is remembered in the newscast is not the lead story. Often, it’s the very last story. The end piece, the last thing the viewer will see. Too many reporters say, “It’s just a feature.” Yeah, right…like “it’s just my career.”

Whatever you do for a living; writing, editing, or photojournalism, your best chance to be creative and take things to the next level is with a feature. Or perhaps you might try using some feature elements in a hard news story. Sticking with a single central character, disciplined writing with plenty of natural sound, and small “gold coins” in a story can work for hard or spot news just as it can for pure feature stories.

b. Please understand what a feature story is NOT. It is NOT the reporter riding the new ride at the local amusement park. That’s filler. It’s almost never found on a public relations release. This is a great misunderstanding among many news directors. Even political stories or economic stories lend themselves to feature techniques. Telling great stories is one reason you wanted to be a reporter in the first place. If that’s not true, perhaps you should have a career in sales.

14. Lighting is for the story, and not for the photographer or the reporter.

a. Great lighting on an interview or a reporter stand-up is a key difference between network news and local news. Those two elements can make up to 50 percent or more of some stories. Shouldn’t they look as great as possible?

This is particularly important as we in news become fully vested in high definition cameras. Lighting will never be more important to anchors, reporters, or subjects than when their image is seen on a huge HD screen.

b. Here are the basics for lighting an interview. Before, the reporters in local news would tell me “I don’t have enough time for that.” I would say, “Do you have four minutes and 20 seconds to improve your overall look dramatically?” That’s about what it takes to set up three lights in an interview setting. Really, I’ve clocked it several times.

c. Here is your lighting mantra, told to generations. I’m just passing it along. The reporter is always between the key light (a large, soft light) and the camera. This is also known as “the reporter sandwich.”

Let’s repeat: “The camera can be on either side of the reporter, as long as the key light is on the other.” This creates shadow side to camera. In other words, the darker side of the interviewee’s face is closest to the camera. The end result of this is called “modeling.” It makes the interviewees face much more interesting. In technical terms, the shadow side of the face is roughly one fourth to one half of an f-stop darker than the brighter side. Another benefit to this is, should the subject have less than perfect skin, you are hiding blemishes, acne and scars from full view.

d. The key light, like all lights, should be on a dimmer for better control. The second light used is the fill light which fills the shadow side just a bit. Then there is hair light or backlight for the hair and shoulders. Finally, a background light illuminates just that. That is four lights total. If you are in an absolute rush, go with a single key light. But avoid the awful “head light”, “Frezzi” or “top light” on top of the camera. This smacks of being unprofessional and just not caring. I use mine, I admit, about twice every year or so, but not for interviews.

e. Now that you know the basics of the four lights, the first thing you do is get rid of the existing light as much as possible. What a blank canvas is to an artist, the darkened room is to the photojournalist. From a dark room you can add controlled light.

f. The subject needs to be out of his big, comfy swiveling leather chair and into one that doesn’t move and has a back low enough that we can see past their shoulders. This is one more way you can build depth and prevent your subject from moving.

g. Now, just because a subject works behind a desk doesn’t mean that they should be interviewed there. Quite often, that desk can be used as a background. Find a background that contributes to the story. If you are outside and your story is on the Humane Society, don’t have the cars in the parking lot in your background: they have NOTHING to do with the story.

h. If you can’t find a decent background, at least throw the background out of focus by opening up the lens as much as possible. This involves using less light on the subject and exposing for the background, thereby opening the lens more. Also, by getting the camera as far from the subject as possible will help get that “compressed” look, as long as the subject has some distance from himself and the wall behind him. By the way, every one of my light kits has a liquid powder that works like a champ. I currently use Dr. Brandts’ “Pores No More.” Put it on and no more shine.

KEEP IN MIND: SHADOW SIDE TO CAMERA.

15. Some sound advice

a. As they say at the National Press Photographers Association Video Workshop, “Mic a dog.” Natural sound is one of the key ingredients that make a great story great: It takes a viewer THERE. It brings them that much closer to the action. You are letting the viewer hear nuances of the moment.

“Mic a dog?” Remember that Frisbee catching dog example (with writing to the corners of the story)? Well, let’s say you really did “mic a dog” and you put the lavalier microphone and the transmitter on the collar of the animal. Now, when he catches that Frisbee, we are right there with him as we hear the “Karunch!” of his teeth biting into the disc. Sound takes you there.

b. While we are on the subject of sound, try to avoid the microphone logo at all times. I not-so-affectionately call it a “pimple on a prom queen.” Microphones are to be heard and not seen. When you see a microphone with a TV station logo on it, you are watching television. When you us a lav microphone and someone is speaking, you are watching a story. Bob Dotson also notes: “It tells the subject in no uncertain terms as to who is in charge, and it is not him.”

c. Quite often the news director will insist that you use the logoed hand-held microphone during all live shots. Here’s how you get out of that one on the really great stories (and you know which ones those are). Give yourself something to hold during the live shot, and then you HAVE to use a lavalier microphone. Save this for the great stories, but it works every time.

KEEP IN MIND: USE A LAVALIER MIC AND AVOID THE STICK MIC.

16. A little more writing on writing

a. Parallel parking is not just for small cars. Say you have a great sound bite, followed by 10 seconds of silence or useless sound, and then another great sound bite. Instead of editing the two bites or pieces of sound together, create a custom piece of track that goes BETWEEN the two bites. This keeps the viewer “in the moment.” Also works great for music, lyrics, gale force winds, and all sorts of natural sound. It’s a custom piece of small track that makes a big difference.

b. Write to “action-reaction.” At the JFK funeral, the horse drawn hearse goes by (action) then JFK’s little son salutes the hearse (reaction). I truly believe that the reaction represents the viewer. I know you can’t have reaction without the action, but I am convinced that the action is often less important than the reaction.

c. Tracks should be no longer than 12 seconds in most stories. Five or seven seconds would probably serve even better. Natural sound breaks bring you “there.”

d. Great news stories, especially feature stories, are “Shakespearean.” Bill Shakespeare knew (I went to high school with him) that you have to make them laugh before you can make them cry.

No, I don’t want viewers to cry, but Shakespeare was on to something. Laughter is an emotional release. If you can get them to laugh early in your story, they are invested in your story. The impact of the serious moments will hit them harder. Then you can bring them back for hope and meaning at the end.

KEEP IN MIND: 12 SECONDS TRACKS AND ACTION/REACTION.

17. Keep investing in your career

a. Walter Cronkite once told me, “Soon as you put your feet up on the desk, you are in for a big fall backwards.” His point is to keep learning and growing. The Poynter Institute in St. Petersburg, Florida (poynter.org) is world class, priced reasonably, and has something for everyone. The NPPA News Video Workshop (nppa.org) is a terrific way for all journalists to improve, not just photojournalists. They preach the fine art of “The Commitment” there. The point is: invest in yourself. It’s your career, not your boss’s. Pay for the seminar if they won’t!

b. Hit the books! I recommend Al Tompkins’ “Aim for the Heart”, Bob Dotson’s “Make it Memorable”, Bob Brandon’s “The Complete Digital Video Guide”, and Charles Kuralt’s “On the Road with Charles Kuralt.” Let them be your guides.

18. Conclusion

a. Care, give a damn. If you don’t, why would the viewer? Really listen and have some passion in your craft. Be a real human being and learn the fine art of just being…quiet. Be a mentor to an intern or a newsroom newbie. Didn’t somebody help you?

Copyright Les Rose 2008-2021. You may not copy without my permission. All views expressed here and in my seminars are my own and not my employer, past or present. If you made it this far, thanks! I want to thank all the folks that taught me storytelling, especially Steve Hartman, Al Tompkins, Bob Hite, and Bob Dotson. And to my children, who tell the best stories on earth.